We are required to comply with local Indian law

October 9

After visiting Palenque, we headed southwest along the Usumacinta River that serves in this part as the border between Mexico and Guatemala. Before highway was constructed in 1990's, the river was the only means of travel in this region. When we stopped to fill up our fuel tanks, I asked how far the next gas station is located. "If you're traveling along the border, the nearest gas station is 3 hours away," told us a man at the pump, adding, "don't expect cellular signal either". It was weird. Experienced on traveling on many roads in Mexico, we knew that gas stations in Mexico could be found almost everywhere. We were in a remote part of State of Chiapas and slowly began to realize that this Mexican region governed is differently.

Driving towards Bonampak, an important Maya archaeological site, we turned into a side road. There was a checkpoint at the intersection. I slowed down, but no one was visible in the dark, the gate was open, so I decided to go on. In a few minutes, I noticed the police lights in the side mirror. We stopped when they finally reached us. To my surprise, the police car had no police signs on a car body. The two young guys had strange uniforms, not a police one. They smiled it was a good sign. The thing was, as the explained, that we needed to come back. Apparently, they did not expect tourists so late. "You should stop and pay," one of them told us. "I'm sorry," I replied. "We will return back and pay if necessary." "How to hell should I know that a fee is required here," I said to Ewa. There were no signs anywhere to indicate this.

We wanted to spend a night at the local campamento, or campground. We found one by the road. I got out of the car in search of the owner. I quickly found a pissing guy by the stairs of the house. He did not notice me, so I waited for him to finish. As it turned out, it was a family business, camping, and beer bar. There were few drunk fellows sitting inside. It was late. We ordered two breakfasts for tomorrow morning and quickly went to beds on Balios' second floor.

We decided to see nearby Bonampak later in the afternoon, so in the morning we drove 20 km directly to Frontera Corozal, a village on the Usumacinta River. From there we had to rent el barco or a boat. In no time, captain Diego led the boat with us in towards the ruins of Yaxchilan, the ancient Maya city on the banks of river. Water was brownish color, riverbanks over grown with greenery. Monkeys ran around the treetops. Guatemala was on our right side. "Do you sometimes meet people crossing the river from Guatemala illegally?" was one of my first question to our guide Francisco who also accompanied us. "We see them every day, they come in search of work," was the answered. "Are you afraid of them?" I was curious. "No, they are good people, very calm." Soon after our guide answered a phone, someone called him. I would not pay attention to such natural behavior these days. This time however I was surprised. "Is your phone working, why we couldn't get a signal all the way all the way from Palenque?" "Check now," he said, "there's a cell tower on the Guatemalan side, but you're right, there are none were we live." Another weird thing here at Chiapas, I thought. The Mexican government is in constant conflict with Chiapas, was it a conscious action by the authorities. No gas stations and no cell phone coverage.

We arrived at Yaxchilan, one of the most powerful ancient Maya states, the main rival to Piedras Negras located 40 km/ 25 miles downriver. Once this city was at war with the most powerful cities is in the Maya world such as Palenque and Tikal. In the years between AD 250 and 900, Yaxchilan transformed into a large urban center with over 120 structures located in three complexes interconnected by stairways, ramps, and terraces. The buildings here characterized are by roof combs and stucco ornaments.

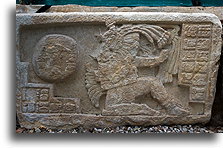

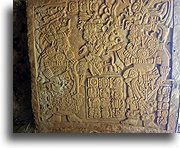

While standing on the large plaza, looking at terraces and platforms skillfully fitted into the hills, it was not hard to imagine all the buildings at the time of their splendor. All the structures around must have been painted red, along with the altars and numerous reliefs. One of the greatest rulers of Yaxchilan was Yaxun Bʼalam IV (Bird Jaguar IV). He erected the most interesting building in the whole city (known today as structure 33) atop of 40 m / 133 feet hill. Climbing many steps, we approached sculptured blocks known as Hieroglyphic Stairway 2 and a rectangular building with high roof comb. It contained two rooms connected by a corbeled vaulted corridor. The central personage in the sculptures and lintels was the great ruler himself. The rooms were dedicated for self-sacrifice ceremonies. Blood served a very important purpose in the Maya culture and was often offered to the Gods by auto-sacrificial bloodletting. Blood was drawn from many different parts of the body like lips, tongue, or ears, but also from the genitals. Variety of tools used in such ceremonies, included mainly obsidian blades and sharp bones. Blood ran down on the bark paper or bird feathers that were burnt to be delivered to the Gods.

Bonampak was another place we wanted to visit. This archeological site is known for the largest mural in the world of the Maya. The frescos here depict war and human sacrifice. Before we approached the ticket booth, some locals we passed pointed out that we had to stop. We ignored them and parked near a place that once was a visitor center. Now it was closed and abandoned, overgrown with plants. There were two people standing outside. One man sold us sightseeing tickets, and said, “ruins are another 8 km away, you need to leave your car here, my friend will take you to the ruins for another 200 peso”. I was extremely surprised by this, “we do not need a lift,” I told him we have a car and we can drive ourselves.” “No, you can't go there alone” was the answer. It must be a scam, I thought. After visiting many archeological places in Mexico, we have never encountered such a thing. It was dangerous and highly suspicious that they want us to leave the car in a place where nobody else parked and the fact that they require a lot of money for a transport in private vehicle. There was no gate, no information board. Absolutely nothing would indicate that tourists could not drive themselves. Together with Ewa, we got back into our Jeep and decided to drive to the ruins ourselves. Almost immediately, the same passenger car that that was supposed to be our transport followed us. They wanted to pass us at all costs, but the road was too narrow, only one lane. They honked constantly, until we parked at the very end of the road. Several angry Indians jumped out of the car that has just followed us. The Conversation was difficult. It became clear that they would not let us visit the ruins of Bonampak. An elderly Indian man appeared suddenly with a wheel wrench in his hands. "If you go to see the ruins, I'll unscrew your wheels," he shouted. The whole situation turned into a dangerous dispute. There was another car with Mexican license plates in the parking lot. "Why can this car drive in here but we can't?" I screamed nervously. "They are allowed, but not you, this is our rule here." At this point, I understood everything. The local community has its own unwritten rules. We came here with our Western mentality, the Western way of thinking and understanding others. Locals, descendants of the Maya, have their own law, not posted nor published, but observed. We had no choice but to turn back.