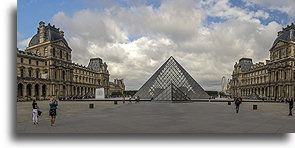

The former royal Louvre Palace in Paris is home to the most visited museum in the world. The visit here is not enjoyable at all. During the summer months, hordes of tourists arrive to see mainly da Vinci's Mona Lisa. Nobody appreciates the painting. After hours in endless lines, you have less than a minute to see the painting above other people's heads. It is definitely not worth spending hours to see one small portrait.

Tens of thousands of works of art are on display at the Louvre. We decided to see only a few of them. Unfortunately, some of the artworks on our list have been temporarily moved to other museums, so we only ended up with six works of art left. We spent the whole day in the Louvre Museum to see them.

The stone stele inscribed with the Code of Hammurabi is an ancient Babylonian legal text, written around 1755 BC. At the time, Babylon was the largest empire in the world that ruled over most of Mesopotamia, which includes parts of modern Iraq, Syria, and Iran. The text engraved on the basalt stele is a set of laws of King Hammurabi. It is the oldest, longest, best organized and best-preserved legal text in human history. This collection of laws and judicial decisions not only served the Babylonians but also taught future generations what justice is.

Text begins by saying that the Mesopotamian gods appointed Hammurabi to make justice. The code includes formulas of judgements for 282 offences. Some rulings say: “If a highborn man puts out the eye of another highborn man, his eye shall be put out.”, “if he puts out the eye of a freed man, (…) he shall pay one gold mina”, and “if he put out the eye of a slave (...) he shall pay one-half of its value”. These principles teach us about the inequality based on the hierarchy in Babylonian Empire. Members of each class have different values. Code of Hammurabi is the first known source of the principle of reciprocal justice, the measure for measure also known to Jews, Muslims and Christians as an eye for an eye concept. The biblical text, Book of Exodus written over 1,000 years later carries the same essential justice drawn probably from the Code of Hammurabi. Text in the Bible instructs us, “But if a serious injury results, then you must require a life for a life. eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, and stripe for stripe.”

Another set of judgments carved into Hammurabi's obelisk contains insights into gender inequality: “If the woman of the upper class dies, his daughter shall be put to death”, “if a woman of the free class dies, he shall pay half a mina”, and “if this maid-servant die, he shall pay one-third of a mina.” These are the principles that will be firmly entrenched in many future social principles and major religions. It is clear that women are always worth less than men of the same class.